I have a basement full of haphazard time capsules, the result of recreational or emergency moving exactly fifty times in my life. Finally, having reached the outer limits of home improvement and cable news, I am working on a long-neglected personal project. While procrastinating on the substance of it, I will admit to obsessing over the micro bits of factual data. One aspect of this involves mapping my daily walk from my apartment to my teaching job, just over thirty years ago in Japan.

The storage compartment in my brain for that time period is damaged and over capacity, jumbled with random Japanese vocabulary words, stressed by the homesickness that comes with living in a foreign country, fatigued by balancing five side jobs teaching Engrish conversation, fragmented by memories of living with my first serious boyfriend, and fried from the trauma of preparing live octopus for dinner.

I can always remember the name of my school—and it’s easy to find on a Google map. But the location of the apartment where I lived is data that was lost on the hard drive of my hippocampus soon after my visa expired.

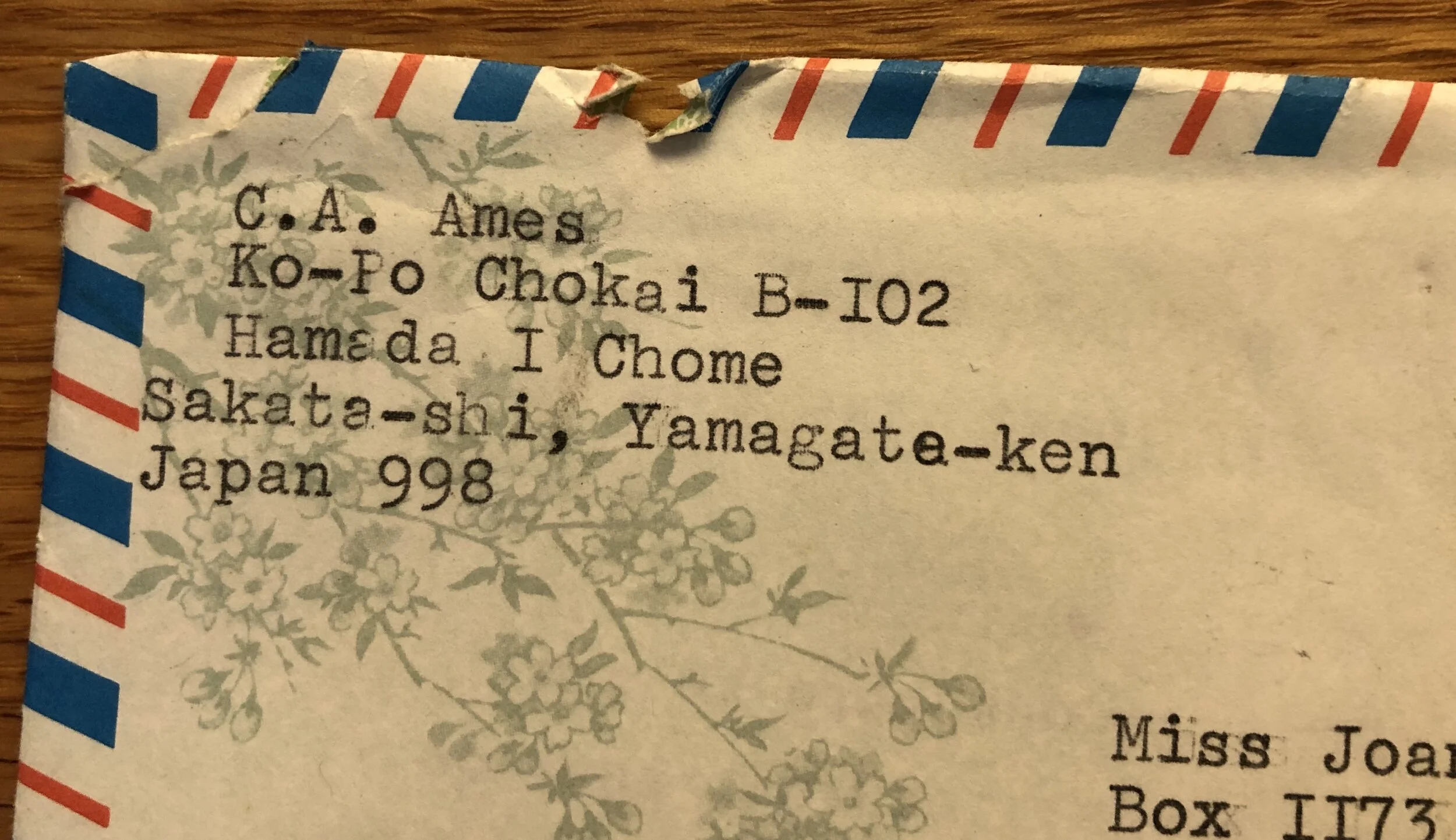

Two clues remain—a photograph of the outside of the apartment complex, and a letter showing at least how we would receive mail. Japanese addresses are complicated. Impossibly cryptic for something like a Google mapping program. Instead of street names, areas are mapped by prefecture (ken), city (shi), ward (ku) and then districts (chome), which are then further parsed into numbers (1 Chome, 2 Chome, etc.).

Sakata-shi is not a beautiful city by any standard. It has its tiny moments of unexpected wonder, but you’d really have to go there to discover them for yourself. If you can imagine the rust belt utility of Erie, Pennsylvania as the gateway to the corn fields of Nebraska, but with rice, salty sea air, and an aging Japanese population, this is Sakata. World War II left little damage, except for one air raid on the city’s port which killed 30 people. The real damage to Sakata came from a 1976 fire which gutted its city center, leveling almost 2,000 buildings, followed by a recession referred to as “the lost decade” due to the collapse of the fabled economic bubble of the 1980s. Most of the post-fire, post-modern architecture is hurried, flimsy and unremarkable, but I still found it to be every inch a fascinating place. Maybe because I am from Buffalo, New York – another port town on the same latitude, a hemisphere away, that had already been burnt down.

The only photo I have of our Sakata apartment complex shows a two-story circa 1985 structure with pale blue vinyl siding and a decorative timber façade detail under a false dormer, like an ersatz Shinto shrine by Robert Venturi. The address on the envelope reads, “Ko-Po Chokai B-102” – a poor translation of a developer’s attempt at urban placemaking, named after nearby Mount Chokai, the active volcano which looms over the city. Building B. Apartment 102. Our chīsai apāto. Our 小さい アパート. Our small apartment. That was our term of affection for where we stuffed the octopus heads with rice before baking them in a Panasonic toaster oven borrowed from the future props department of the set of Lost.

The next line of the address reads, “Hamada 1-Chome” which indicates the Hamada ward and the first Chome district (of which there are 11) of Sakata-shi in Yamagata-ken. But when you look at this district on a map you just see an overview of grey toy building blocks of varying shapes and sizes. You can look at the satellite view of the area, but then you just see a dense quilt of multicolor metal roofing material, with a few hints: ロイヤルネットワーク(株) – dry cleaner or 稲荷神社 – Inari Shrine.

I think I remember that shrine. Yes, there was a small shrine near our building. I remember the word Inari.

Dry cleaner? We hung our t-shirts on a plastic rack off the balcony, and our work clothes wreaked permanently of cigarette smoke from the teachers’ lounge and our favorite Izakaya. I don’t remember anything about a dry cleaner.

Over the course of several weeks my desire to find the precise location of this apartment building was bordering on psychotic obsession.

If I could just locate the building on a map, see it again in its contemporary state, it would surly trigger a flood of deeper related memories of that era of my life. Everything would fall into place. This would be my home screen, and I could then walk freely through the stored data of my lifetime. I could defragment my hippocampus and run the update in my amygdala, cerebellum and prefrontal cortex. I could place the physical photographs and letters into a clean 11x17x3 inch acid-free storage container with the calm that accompanies a journey to better know myself, accepting my history, and facing my present.

Every few days I’d give up but then come back to it, dropping a fresh map pin on that shi, and ku and chome, alternating between map and satellite and street view. Walking that little tilting yellow Google Maps man up and down streets, block by block, turning around, going back, going too far, tilting upward, turning back again, losing control of the cursor, ending up 500 miles south, recalibrating, starting over, stopping short, facing an empty lot, dooming that tiny yellow man to life trapped in a densely-built 200-square-mile labyrinth until I got sea sick.

It’s okay, I tried to reassure myself. The building is probably gone. It was only made of paper, after all. Move on.

I’m not up for reading the box of letters that will surely be cringe worthy. I transferred my obsession to the piles of photographs, categorizing them into thematic piles: classroom, sightseeing trips, friends, drinking with friends, drinking with friends at obscure regional festivals, and so on.

But one photo didn’t fit. A photo of an older Japanese woman walking down a very narrow, curved street. I immediately remember taking the photo and why I took the photo. The street was so impossibly narrow that if you came upon another car, you could not pass. You’d have to defer to the oncoming car after an awkward and comic display of deferential etiquette that is uniquely Japanese. One of the cars would backup into the closest driveway while apologizing profusely and repeatedly. I wanted to remember the comedy of those moments. And the ubiquitous walls and fences of my neighborhood, and so much of residential Japan. These were very pedestrian walls by Japanese standards. But these particular walls—a simple wooden slat fence and a pre-fab concrete wall—had become significant to me, helping to mark the path from our chīsai apāto to the school where I spent days breathing in the mixture of methanol and isopropanol alcohol wafting from the mimeograph closet across from my desk.

Did I remember that concrete fence from a dusty neurological file, thirty years past expiration? Or was it the particular curve of this little street? Or had I just seen this wall, this street, while touring the video game screens of Google Maps?

Now it’s not like I went totally insane. I mean, I did sleep and eat. I did watch cable news. I did feed the cats and water the plants. I read things. Other things that have nothing to do with any of this. I thought about starting Animal Crossing to take my mind off this entirely. But then I remembered the hard fall coming down of a circa 2001 addiction to Age of Empires. I planted flowers instead. Baked a cake. But this broken link was still spinning in the background of my mind.

Back to the grid. If that fence is there now, I’ll find it. And I’ll find the apartment building. And I’ll remember everything I need to remember. I go back in. I drop the pin on the school. I walk yellow man down each block of Hamada 1-Chome, tempering what I anticipate will be disappointment, but fully committed to seeing this through.

Yellow man turns a corner. Boom. Adrenaline rush. Hard exhale. There it is. The very spot. The old woman is gone now. Probably dead. But this is it. The very Google street view intersection matching the only known photo of my daily path from thirty years ago.

To the left, the mundane elegance of the former wooden fence has been replaced by a poorly conceived array of faux stacked stone, brickwork, concrete slab and metal. There on the corner is a bed of garish impatiens that you might expect to see in a Rite-Aid parking lot in the U.S., and there is a long course of plain concrete and metalwork fence drawing the property line. Even the house has been replaced.

To the right is the wall I remember so well, made from plain cinder blocks, mixed with breeze blocks cut with a repeating decorative pattern, and topped with smaller decorative pre-fab concrete intended to mimic traditional Japanese clay roof tiles. Just the kind of physical evidence you’d expect to find in a traditional working-class city that was forced to rebuild from a fire during a recession. I must have walked past this concrete wall over 900 times, over 300 days, maybe walking past the old woman enough times to work up the nerve to say, “good morning.” Ohayōgozaimasu. おはようございます.

It’s hard to walk away from this corner. But now I know where to go. Just down the street to the left, as far as the Kirin vending machine, look up and spot the giant kanji font on the side of Ko-Po Chokai A. Walk back through the parking lot to Ko-Po Chokai B. There is the rough-hewn timber under the false dormer. There are the sliding glass doors and railing where we would air out the futon.

Don’t ask me why this minute detail was so critical. It just was. And now, having nearly reaching the last possible outpost of procrastination, the last stop is rebooting and letting it run for a while to see if it works.